December 15, 2025 Mr.Huscher

4. Before Masterclasses, 19th-Century Pianists Fought "Duels"

The intense personal expression Beethoven unleashed on the keyboard soon found its public, competitive outlet in the rise of the "virtuoso." The 19th century became the era of star performers, whose technical sorcery dazzled audiences across Europe. Different schools of technique emerged, led by figures such as Muzio Clementi, hailed as the "father of technique," and Carl Czerny, whose etudes remain a rite of passage for piano students to this day.

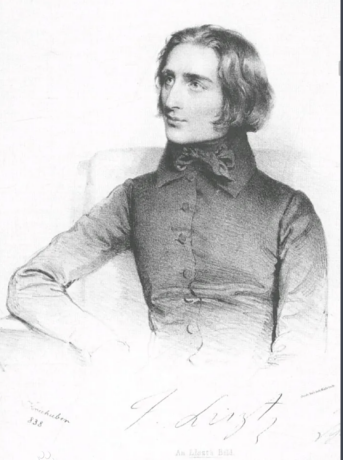

The atmosphere was fiercely competitive, and the primary stage for this rivalry wasn't the modern masterclass, but public musical duels. In the salons of Vienna and Paris, pianists were often pitted against each other to determine who possessed the more brilliant technique and capacity for improvisation. An anecdote from the time tells of pianist Abbé Gelinek informing his father of an invitation to a party where he was expected to "break a lance" in a musical battle against a foreign pianist. This culture of public spectacle culminated in Franz Liszt, whose influence was so profound that playing from memory—once considered a marvel—became the "self-evident rule" for all serious performers.

5. For Romantics, Emotion Was Paramount (Form Was Secondary)

This new level of technical mastery provided the necessary tool for the next great shift in musical philosophy. The virtuosos had built powerful engines of expression; the Romantics would now provide the fuel. The transition from the Classical to the Romantic period was a shift from objective beauty and formal perfection to subjective emotion and personal expression. This core difference can be defined by a powerful distinction:

In "Classical" music in this sense, form was primary, content secondary; while in "Romantic" music, content was primary, form secondary.

Franz Schubert was the perfect embodiment of this change. The "speaking soul" and "true dramatic sense" of his musical sensibility first shaped his immortal Lieder, which then "also gave character to his piano music." Although he continued to write sonatas, he found traditional structures did not always satisfy his lyrical imagination. Because sonata form "no longer fully satisfied his needs as a medium of expression," he created new, freer forms like his Impromptus and Moments Musicaux. These works were not bound to rigid formal schemes; instead, they followed the organic flow of feeling, much as his songs followed the emotion of the poetry. This liberation of content from form, which placed personal emotional experience first, paved the way for the intensely personal and poetic piano music of Robert Schumann and Frédéric Chopin.

From an unrealized dream in the minds of Baroque composers, to a mouthpiece for Romantic passion, to the centerpiece of the modern home, the piano has never been a single, static thing. Its history is a dynamic story of reinvention, a dialogue between artists who demanded more and innovators who gave it new voices. The five truths we have explored reveal an instrument perpetually shaped by the tides of culture, technology, and human expression.

The piano is more than just wood, strings, and hammers; it is a living chronicle of our evolving relationship with music. As technology and art continue to merge in unpredictable new ways, one question remains: What will the next great transformation of the piano's voice sound like?